"I am all fucked out. That goddam woman has absolutely screwed me from one end of the room to another for three goddam nights."

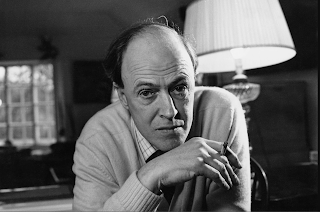

While that's not from James and the Giant Peach, I think it's safe to say Roald Dahl enjoyed himself a peach in the Nic Cage sense. Jennet Conant's The Irregulars is a delightful read about an incredibly dark time focusing on the efforts of the British Security Coordination (BSC) to draw the US into WWII, the covert activities going on throughout the US to this effect, and their involvement throughout the course of the war. The cast of characters keeps the book moving at a quick, fascinating pace—though without a grounding in the era's history, these figures might run together and make comprehension difficult. It is also important to remember that, although we look back on it as a righteous war, at the time, there were many (the political right and Republican party, in particular) who advocated staying out of WWII altogether and allowing Hitler and the Axis powers to remake the world as they saw fit.

At least in part spurred on by the fact that information remains classified, covert activities during WWII are a fascinating field of study. It certainly doesn't hurt that those involved include the political (FDR, LBJ, Clare Boothe Luce, Henry Wallace, Churchill), the entertainment industry and artists (Ian Fleming, of James Bond fame, Sir Chrisopher Lee, Roald Dahl. and Ernest Hemingway, who kinda gathered information on Nazi sympathizers in Cuba but mostly just wanted fuel for fishing trips. Hemingway also received aid from Dahl to be on-sight to report on D-Day and later, on receiving a copy of Dahl's Over To You, read it and returned it with the comment he "didn't understand [the stories]."), and the business realm (Walt Disney, William Stephenson, David Ogilvy, Charles Marsh).

As Conant discusses in her introduction, her intention in the book is to try and put the reader into the shoes and experiences of a mid-to-late-twenties Dahl as he experienced the US, where he was sent to work in the embassy after being declared unfit for the RAF. Prior to this, Dahl had been a pilot despite his ~6'6" frame and the small size of the fighter planes; the crash that put him out of action would ultimately help to sell his first story and net him a $1k payday ($18.9k today, minus 10% for an agent's fee; promptly lost to Harry Truman, as an earlier fun fact post mentioned).

Like many in WWII who wanted to serve on the front lines, Dahl strongly disliked being invalided and moved from the front. He was eager to serve in any capacity available to him, thus being happy to sign up for covert work when given the chance. And, as the book happily points out, he was perfect for the job: like several of those picked for these covert jobs, he was ostensibly terrible for the job and a security liability susceptible to letting sensitive information slip. This helped to transmit information without arousing suspicion.

In the US, Dahl is connected with one Charles Marsh, a newspaper publisher and oil entrepreneur from Texas who was a bit of a local kingmaker; one of his other proteges was some nobody named Lyndon Baines Johnson, later to be known to history as El BJ and famous for his lesser-known children's novel Jumbo Johnson and the Trousers That Just Wouldn't Fit. It is Marsh who helps Dahl to get his first story published in addition to helping him with social connections in Washington. Despite his best efforts, Marsh had found his local influence in Texas had not translated to the nation's capital.

Dahl's liaisons, like Ian Flemings', were often much more mundane than their gripping stories would lead us to believe; as the opening picture and caption indicate, a decent chunk of Dahl's job involved sleeping around. The woman in question he was sleeping with for that caption was Clare Boothe Luce, wife of the famous newspaperman Henry Luce (of Time fame) and, along with her husband, a notorious isolationist—like many republicans, in an eerie parallel to their reluctance and foot-dragging on Ukraine today (appeasement worked so well with Hitler, after all). In the tradition of James Bond, and perhaps part of where Fleming drew his inspiration, after shifting from the front lines to covert work, Dahl's biggest fears also seem to have changed: where he once feared armed Nazis, now he feared an STD panel or a letter from the paternity department of the Maury Povich show.

"Roald, you said Ms. Booth fucked you—the lie detector test determined she won't be done fucking you until you receive the back child support bill."

We also get a glimpse at some of the covert work undertaken and how much it, frankly, bordered on comical at times despite the seriousness of what they were doing. For one success: after an isolationist Republican gave a speech, it was arranged for him to get a postcard reading something to the effect of 'The Fuhrer thanks you for your support!' just as newspapers surrounded him, creating a terrible image; another attempt backfired when an attempt to flood a Charles Lindbergh event with fake tickets and get people driven away ended up leading to an above-capacity audience with more would-be attendees on the streets outside in support of Lindbergh's extremist appeasement. It brings to mind some of the goofier tricks played by Nixon's CREEP, like ordering pizzas to be delivered during victory speeches and the like, which belies the gravity of what these antics are for and what is going on in Europe—it also might be read to give a glimpse of the whimsical, if sardonic and dark, children's stories Dahl would go on to write.

From FDR and Winston Churchill's friendship (one of Churchill's few redeeming qualities; FDR, as ever, remains an enigma and a cipher in Conant's telling, a man who seems to reflect whatever one wants to see in him) to Dahl's friendship with Eleanor Roosevelt, including helping her to get photos of a son serving in Europe, or glimpses into J. Edgar Hoover's paranoid, suspicious mind, we see the human side of figures who all too often are subsumed by their roles in our stage play world.

We also get an interesting insight into the unexpected relationships formed over the course of the Second World War, which led to things like the business dealings between Walt Disney and Roald Dahl, or David Ogilvy's involvement in spying activities before going on to found his advertising agency. In the overlapping field of entrepreneurship and spywork, we also encounter William Stephenson—a Canadian who became a self-made millionaire by patenting a can opener he filched during an escape from a WWI German POW camp. Sometimes, life really is stranger than fiction.

All around, Conant's book is a fun, easy read; similar to Bess and Harry, it isn't the type of book you're picking up for a deeper understanding of geopolitics or deep, nitty-gritty history, but it's a fun beach read packed full of anecdotes and interactions between historical figures.

Comments

Post a Comment